The pleasures and pitfalls of rendering interpretations in layperson’s language

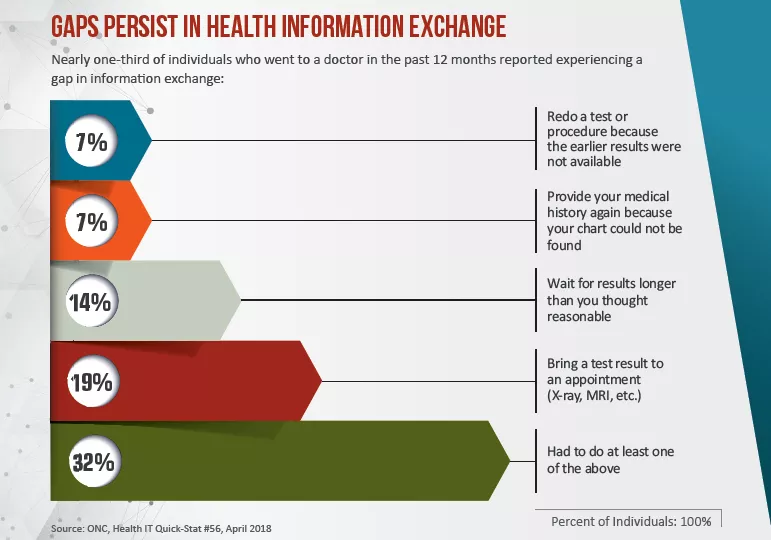

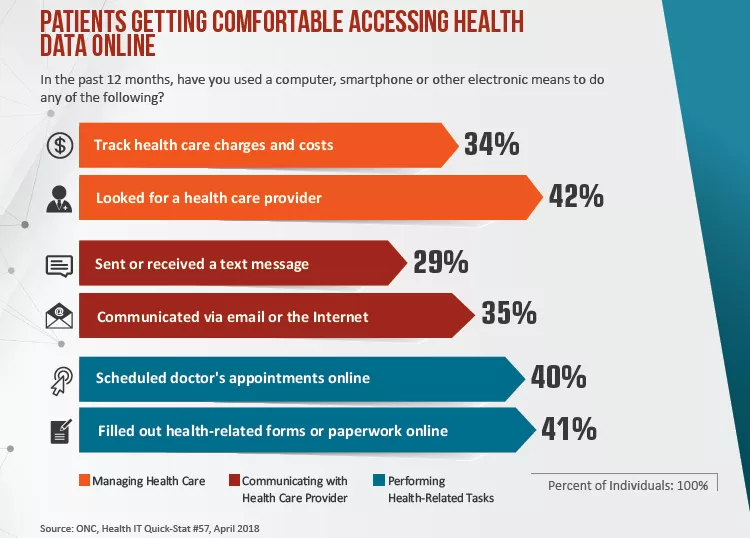

When it comes to monitoring their own health, many of today’s patients expect fast access to all their info. Why wouldn’t they? Wearables record how many steps they walk each day. Smartphone apps tell them how much sleep they’re getting each night. If they have a chronic condition, chances are there’s a specialized app for it. And on top of all that, according to the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology, nearly three-quarters of U.S. hospitals now offer EMR-linked patient portals with view, download and transmit capabilities.

To patients who embrace these opportunities, craving the data and even applying the results to their lifestyle choices, medical images and reports register as being of a piece with all the rest of mHealth.

Few would argue that they’re wrong to see things this way.

“Patients seeing their medical records and their images and reading their radiology reports—on the whole, I think it’s a good thing,” says David Hackney, MD, a radiologist a Boston’s Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and professor of radiology at Harvard Medical School. “It’s about them. They have the right to see every bit of it.”

Of course, images are one thing. Most patients like to look even though they don’t know what to look for. Radiology reports, however, invite word-by-word scrutiny. Hackney acknowledges that the language of radiology can be daunting and sometimes frightening even for highly educated, sophisticated patients with Google at their fingertips.

“Last week I read a scan and mentioned some incidental, insignificant thing that was there,” he explains, adding that the untroublesome finding was a pineal cyst. The patient researched the term online and became alarmed. “I spent a lot of time trying to tell this patient that the finding is completely insignificant, that it didn’t matter for their life,” says Hackney. “Then I tried, with less success, to explain what it actually was.”

Despite the occasional cases of misplaced anxiety, Beth Israel has long given patients ready access to all their medical records, including radiology images and reports. And Hackney is confident that the advantages of such clinical transparency outweigh any drawbacks.

He’s not alone. Numerous surveys and studies have shown high patient interest in radiology reports. And, as far back as 2011, approximately 90 percent of radiologists were incentivized by CMS to improve access to health data—including via radiology reports (reference: Lee et al., “Implications of Direct Patient Online Access to Radiology Reports Through Patient Web Portals,” JACR, December 2016).

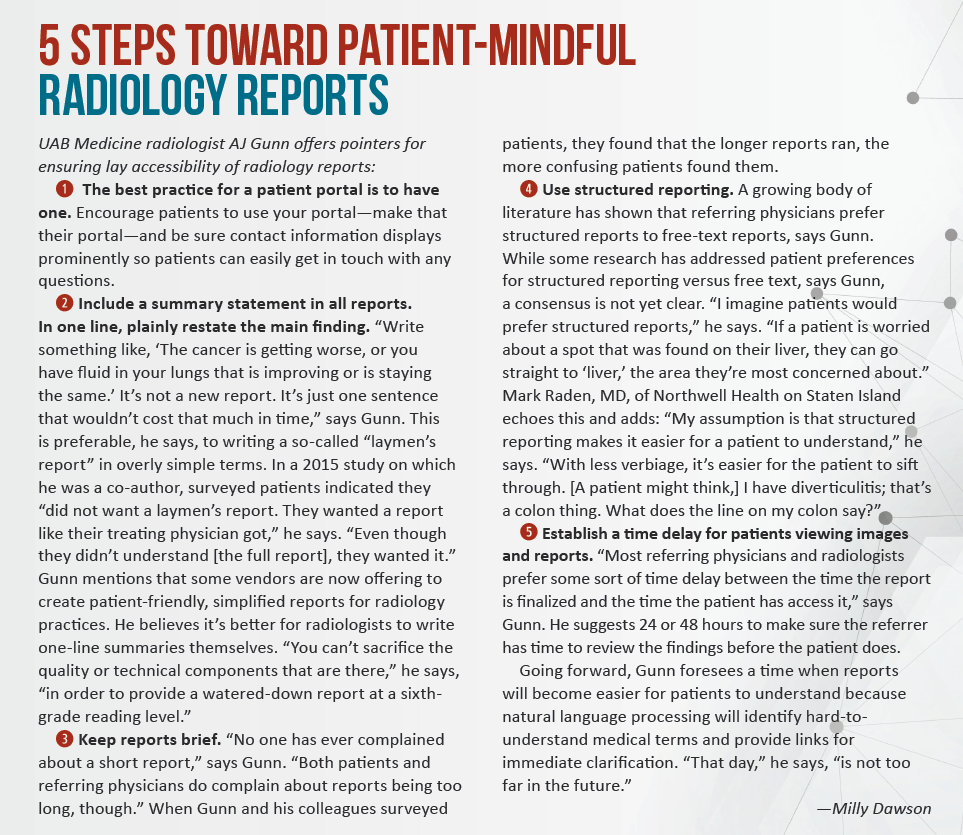

The momentum is clearly in favor of greater direct-to-patient radiology reporting. However, the consensus among experts and observers seems to be that radiologists need to think like a layperson on the receiving end. In most cases this means checking for clarity over ambiguity, anticipating potential trip-ups and generally taking care to minimize the risk of stressing patients out rather than filling them in.

Several schools of thought

When patients see their radiology images and reports, they often have questions and concerns that no clinician is better qualified to address than a radiologist. So asserts Andrew “AJ” Gunn, MD, an interventional radiologist and assistant professor at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB). “I don’t think we can rely on primary-care doctors or non-imaging experts to be able to explain the subtle detail of the wording used in the report,” he says. “Sitting down with the patient to explain can be really helpful.”

Doing so is surely easier for interventionalists and breast specialists than for other diagnostic rads. Either way, a slightly different take gets an airing in the October 2017 edition of JACR. In an opinion piece titled “Patients Should Not Have Unchaperoned Access to Radiology Reports,” Andre Konski, MD, MBA, professor of clinical radiation oncology at Penn Medicine, makes the case that patient access and review of radiology reports should take place only when a qualified care professional—not necessarily a radiologist—is available to serve as an information chaperon.

“I am not arguing patients should not have access to their EHR,” Konski writes, “but they should have access to them with their physicians, who are able to explain the findings on the report in a way the patient can understand and in the context of the patient’s disease course. Only then can unintended consequences of patient distress be averted.”

JACR presents Konski’s argument as a counterpoint to a piece in the same issue titled “Let Patients Decide How to Get Their Radiologists’ Reports.” Its author is Andrea Borondy Kitts, MPH, MS, a Connecticut-based patient advocate who lost her husband to lung cancer and blogs at JACRblog.org.

“I propose that patients be able to select their desired methods of receiving both images and radiologists’ reports at the time their tests are ordered,” Borondy Kitts writes. “As we transition to patient- and family-centered care in radiology, it is important to provide options for patients to receive the main product provided by radiologists: their expert opinions on what the pictures show and what these mean for the patients.”

Reports in context

Radiology reports don’t exist in a vacuum. As U.S. healthcare continues adopting value-based payment models using use patient engagement and satisfaction as key metrics, radiologists are exploring new ways to add value.

“‘Value’ is not just a new corporate buzzword [but rather] a fundamental goal of the new healthcare, which seeks to improve the patient experience while maximizing outcomes and minimizing costs,” Gunn and colleagues write in a 2015 study published in the American Journal of Roentgenology.

The authors describe how they created a patient-centered radiology practice by establishing a diagnostic radiology consultation clinic at Massachusetts General Hospital. Lead author Mark Mangano, MD, and colleagues surveyed patients who’d had one of three types of imaging and then were given an opportunity to discuss their results with a radiologist. Some 88 percent opted to have the radiology consults, and as a group they rated the session as “very helpful” (mean, 4.8 on 1–5 scale). All participants who took the consult said they’d do it again. What’s more, all were able to correctly identify the radiologist as a physician who interprets medical images.

Among their ideas for growth in this area, the authors name reviewing specific report terminology with patients “to clarify and potentially reduce patient anxiety while supporting referring physicians.”

Well and good, but are radiologists on board? Some are, some aren’t, Gunn suggests. To those who see patients reading radiology reports as a thing to avoid as long as possible, he offers a reality check: The sooner you accept the inevitable, the sooner you’ll be giving yourself a competitive edge.

“You would anticipate that, as we transition to value-based care, practices and radiologists who invested in this early on would be ahead of the game,” Gunn says. “The question is, how do we demonstrate value?” The answer has less to do with cranking out as many reads as possible, he adds, than with supplying expert clinical guidance.

It pays to go face to face

The time radiologists spend discussing radiology reports with patients is not reimbursable. But that shouldn’t be a disincentive to have the conversations, as the time commitment is modest, according to the authors of a study posted online in JACR this past January, “Radiologists’ Experience with Patient Interactions in the Era of Open Access of Patients to Radiology Reports.”

Led by Jieming Fang, MD, a radiologist with Boston’s Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, the researchers surveyed 94 radiologists working at that medical center about their patient interactions. They found fewer than one-fifth of respondents had interactions requiring more than 15 minutes, and they cite prior studies showing the average discussion times ranging from 7 to 10 minutes.

“[M]ost radiologists at our institution would welcome more direct interactions with their patients,” they write, adding that “the vast majority of these radiologists do not subjectively perceive these interactions to be detrimental to their normal workflow.”

Asked about the time commitment needed for going face-to-face with patients, Gunn emphasizes that today’s radiologists face plenty of competition. “Why will the referring physician send patients to your group versus another group?” he says. “What service do you provide in addition to that read?” He posits that the return on investment is likely to take the form of loyalty from both patients and referring physicians.

Mark Raden, MD, a radiologist with Northwell Health and Staten Island University Hospital, agrees. Time spent discussing images with patients is a good business investment and fosters loyalty, he points out. “We let them know that we exist—‘I am Dr. So-and-So and I’m specially trained,’” he says. “They’re not just getting an MRI of the spine and then seeing a bill with some guy’s name on it.”

After talking with their radiologist, Raden adds, patients are likely utter some variation on a statement every physician wants to hear: “Next time I need this service, I’m coming back to you.”

Words that work for patients

How best to provide patient-friendly radiology reports? Research into that question is ongoing. In a survey-based study published in in the November 2017 edition of JACR, Ryan Short, MD, of Duke and colleagues looked at the use of crowdsourcing to assess the effectiveness of an in-teractive radiology report available to patients online.

They found the format of the report, including not only terminology but also display components—hover-over text options, popup notations and so on—likely influences the effectiveness of the end aim of patient access to radiology reports: communication.

“Patient-centered reports, such as a simple-language patient letter or a web-based interactive radiology report, may offer advantages in patient communication over the standard radiology report, including improvements in patient engagement, report comprehension and satisfaction with radiologists,” Short and co-authors write.

Whatever methods of report access go on to become best practices, Gunn believes the healthcare market probably won’t be kind to those who take a wait-and-see approach.

“Do you want to be involved in a practice that is sitting still and not moving forward?” he asks, rhetorically. “If you hunker down in hopes that this trend is going away, you will be left behind.”