Structured Reporting: Resistance Is Futile

Structured reporting is to radiology as the baseball diamond is to Ray Kinsella, the fictional farmer played by Kevin Costner in Field of Dreams. “If you build it, he will come,” a disembodied voice whispers as Kinsella walks through a cornfield. Over the years the iconic line has often been misquoted as “they will come,” and that makes it all the more fitting. For proponents and enthusiasts of structured radiology reporting have long hoped it would gain widespread if not universal acceptance.

If you build it, the thinking has gone, radiologists will flock to it.

Who wouldn’t want greater consistency in substance, style and actionability to referring clinicians? And in recent years, refinements in software have continually advanced structured reporting’s strides toward standardization. But what worked for fictional Ray Kinsella hasn’t panned out for real-world radiology. A substantial number of radiologists have persistently avoided, thwarted or quietly rejected structured reporting.

Nevertheless, the resisters’ days are numbered, insist the experts, as structured reporting’s advantages so thoroughly outweigh its drawbacks. The question now is how to get from lukewarm reception to universal embrace. The search for an answer must begin with some of the most common complaints voiced by structured reporting stragglers.

The Detractor Factor

The Detractor Factor

One common objection stems from the widespread preference for narrative style based on the principle that “the specialty is consultative and, in reports, we’re answering questions.” That’s the studied observation of Bibb Allen Jr., MD, the Alabama radiologist and past ACR president who now serves as chief medical officer of the ACR’s Data Science Institute.

Some radiologists, Allen observes, recoil from the “point and click, point and click” ungainliness that structured reporting injects into workflow. Others find themselves paying undue attention to the structure itself, Allen adds, whereby the tool becomes a distraction from the radiological ideal of “eyes on images.”

Also among the reticent are radiologists who feel structured reporting hinders rads from applying the full breadth of their knowledge. In a paper published in the January 2018 edition of Academic Radiology, Ganeshan et al. note that many radiologists “value their freedom of expression and may perceive structured reporting as an attack on their autonomy and the art of medicine.” Some believe structured templates encourage the commoditization of the specialty, the authors add, “and can downgrade the quality of sub-specialist reads by limiting the scope of what they can include.”

Other motives for avoidance aren’t hard to find. Tucker Johnson, MD, of the Mayo Clinic tells RBJ he’s heard from a number of radiologists that structured reporting forces them to order their reports in a counterintuitive manner, to the detriment of the final product. For example, a structured report may place a notation about the presence of a soft-tissue sarcoma in the chest wall only at the end of the findings section.

“In other words, the fixed template doesn’t always allow radiologists to create a well-crafted, well-organized ‘story’ about what they are seeing,” Johnson says.

Similarly, Travis Browning, MD, of UT Southwestern Medical Center and Parkland Memorial Hospital in Dallas, has heard a litany of gripes leveled at structured reporting. Some radiologists feel systematizing reporting “takes away the art of reading” images, he says. Others have insisted that structured reports fail to reflect potentially important nuances, he adds.

Browning, who serves as a director of quality at UT Southwestern and of informatics at Parkland, says he’s also heard: “Structured reporting slows me down,” “My way is faster or adds more value,” “My referrers like it better the old way”—and even “I just don’t want to change.”

Undeniable Upsides

Undeniable Upsides

Against a tide of misgivings with so much negative momentum, radiology practices and departments may blanch before pushing members to use structured reporting. Sources interviewed for this article were sympathetic. However, they agreed, radiology leaders would be wise to boost radiologists’ buy-in on structured reporting by clarifying its benefits, beginning with how far standardization can go toward improving the caliber of reports and, with it, the quality of care.

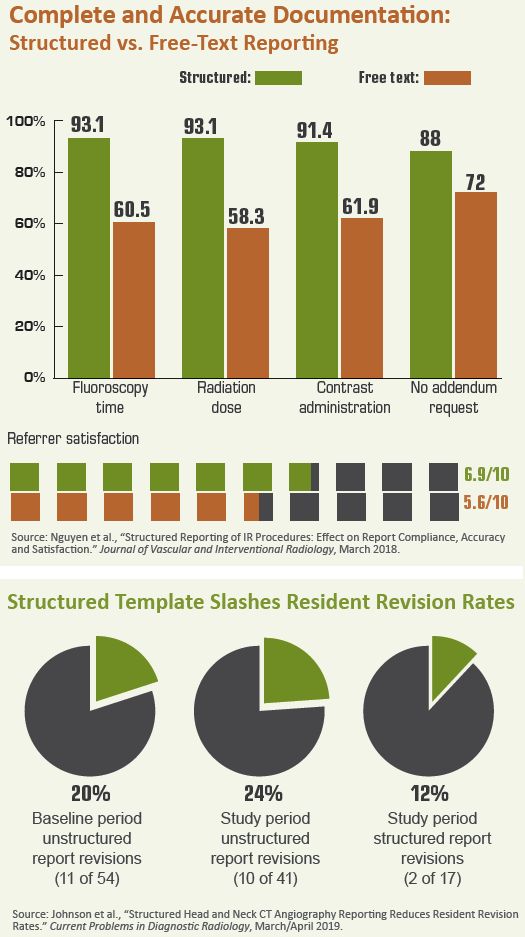

The consensus is that more consistent clarity, terminology, completeness and incorporation of evidence-based decision support—all attributes of structured reporting—can cut diagnostic errors, improve report accuracy and reduce the potential for inadvertent omissions.

Backing this view is a 2018 case study from the Mayo Clinic lead-authored by Johnson and published in Current Problems in Diagnostic Radiology. The researchers, including senior author Amy Kotsenas, MD, looked at revision rates for studies performed by residents with and without the use of a structured template over a two-month period.

The team found the structured template cut revision rates nearly in half.

“We believe that structured reporting can help reduce reporting errors, particularly in terms of typographical errors; train residents to evaluate complex examinations in a systematic fashion; and assist them in recalling critical findings on these examinations,” Johnson and colleagues conclude in “Structured Head and Neck CT Angiography Reporting Reduces Resident Revision Rates.” They add that, based on the results they achieved, along with positive feedback they received, “we plan to identify additional complex cross-sectional examinations that may benefit [from] structured templates at our institution.”

At 18-state, 1,200-radiologist Radiology Partners, structured reporting is seen as a reliable means to achieve data-driven quality improvement. Measurable steps toward that aim include more accurate tracking of outcomes and more consistent application of best practices, according to Dean Chauvin, MD, who practices in Houston and serves as Radiology Partners’ national director of interventional radiology.

Quality improvement informed by data “was our impetus to make the move to structured reporting in the first place,” Chauvin says. “With structured reporting we can go back and extrapolate data to see what percentage of the time we’re meeting an objective and what percentage of patients had what outcome,” he says. “We can find statistics we need to prove what we are claiming to payers and hospitals. We don’t need to go through 3,000 records manually.”

What Referrers Prefer

Ganeshan and co-authors similarly stress the importance of this aspect, especially as it relates to reimbursement, in their January 2018 Academic Radiology article, “Structured Reporting in Radiology,” which reflects the views of a task force on structured reporting convened by the Radiology Research Alliance of the Association of University Radiologists.

“The future where we are reimbursed based on the inclusion of particular words in our reports is already upon us,” the authors write, adding that data pulled from structured reports can provide the evidence needed to maximize reimbursements under CMS’s Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS).

Then there’s the perpetual challenge of satisfying—and improving relationships with—referring physicians, whom proponents say increasingly favor structured reports. “One way to gain buy-in from radiologists is to demonstrate the preference of the ordering providers,” Johnson says. “In some cases there will be a preference for structured reports.”

Allen concurs, noting that many referring physicians believe structured reporting can allay their concerns over ambiguity, off ering a clearer picture of how to move ahead with courses of treatment and follow-up.

Helpful Visuals

Helpful Visuals

Another incentive for radiologists to utilize structured reports: They’re readily augmented with elements that provide additional information for—and hence value to—referring physicians.

“One of the ways radiologists are judged as being effective is via their communication ability,” Johnson points out. “Confi dence statements, differential diagnoses and follow-up recommendations are all ways of bringing improved clarity to our reports and helping clinicians navigate potential next steps in an increasingly complex radiology field.”

Johnson further believes there are particular structured reports that benefit greatly from the inclusion of tables, charts and graphs. He cites bone mineral density (DEXA) reports as a prime example, as DEXA exams are performed similarly each time and the important results are numerical. Templates can ensure the referrer sees site of measurement, graphical references for age and tabulated results.

At Mayo, certain structured reports make space for references to incidental findings. “For our structured lung cancer screening report, we have ‘potentially significant finding’ and ‘incidental finding’ headers separate from the main topic of indeterminate pulmonary nodules,” Johnson says. “I believe it helps to organize the report and offers clinicians a quick place to look and see if there is anything else they need to worry about.”

Browning, too, is a fan of tables, charts, and graphs in structured reports, although he notes that graphics can be cumbersome to create and transmit because of the lack of interface between electronic health records (EHRs) and HL7. Once EHRs can display these elements from third-party applications, incorporating them into structured reports will become a more streamlined process, he says.

Inevitable If Not Imminent

Inevitable If Not Imminent

But extolling the benefits of structured reporting, delving into standardization and incorporating multiple components into structured reports are not the “be-all and “end-all” of achieving radiologist buy-in. Less complex strategies play a role in pushing the envelope, too. Case in point: At UT Southwestern Medical Center, feedback on radiology reporting templates is solicited on a regular basis. A five-member committee meets monthly to discuss this feedback, then directs (or vetoes) modifications to the templates.

“If radiologists feel they have a voice in the implementation of structured reporting, they will be more inclined to buy into the process,” Browning says. “You can’t craft the perfect structured reports in isolation or a vacuum. You have to design them to meet the needs of radiologists as well as referrers and patients. You can’t ignore what radiologists have to say and expect them to [embrace] structured reporting. We are always evolving the report templates based on their feedback.”

Browning also has discovered that allowing flexibility and transitioning only gradually can go a long way in bringing along stragglers. “A phasing-in with a few structured components at a time, rather than a big move on day one, helps people get more comfortable,” he says. He adds that UT Southwestern’s radiologists are not forced to use structured templates—but most do, and the expanding adoption owes much to the shift’s pick-your-own-pace approach.

“We started with a format of, ‘Is it this or is it that,” he says. “Then we standardized the content, and now the elements are discrete. It was a smooth changeover.”

Chauvin says Radiology Partners practitioners were told that, if they truly did not care for structured reporting once it was implemented, they could stop using it. “For about two or three weeks, they truly hated it,” he says. “Then they got onboard.

Going forward, radiology practices and departments may need to put their money where their mouth is when it comes to garnering acceptance of structured reporting. “In the future, if reimbursement is tied to how some reports are dictated,” Johnson says, “I don’t think it would be unreasonable to tie financial incentives and penalties to meeting this standard.”

Whatever it takes, the day of universal structured radiology reporting is inevitable even it’s not yet imminent. If you build it, they will come.

Or, as Allen puts it, and not in a whisper: “It’s going to be one more Imaging 3.0 tool for radiologists to provide more value to patients and the healthcare system as a whole. The sooner we’re all on board, the better.”