Researcher on the Trail of the ‘Poster Child’ for Imaging Overutilization

Whenever advanced imaging for low-back pain gets knocked as the “poster child” for overutilization in U.S. healthcare—not an uncommon occurrence—the context of the charge tends to waft away, unconsidered. That’s problematic. To be sure, lumbar-spine MRI in particular has a dicey cost-benefit proposition all its own. The scan’s technical component alone can ring up a bill north of $3,000.

However, the initial outlay can end up looking like nickels and dimes when compared to the high price paid for too much follow-up care generated by the scan.

Jeffrey Jarvik, MD, MPH, lead researcher in the eagerly anticipated (and nearly finished) “Lumbar Imaging with Reporting of Epidemiology” (LIRE) study, discussed this angle of the story in a recent interview.

“Spine imaging is sort of like a gateway drug in that it opens the door to everything that happens downstream,” says Jarvik, a professor of radiology, neuroradiology, health services and neurological surgery at the University of Washington in Seattle. “It potentially leads to questionably needed interventions, which can raise the question of whether the spine imaging was necessary in the first place.”

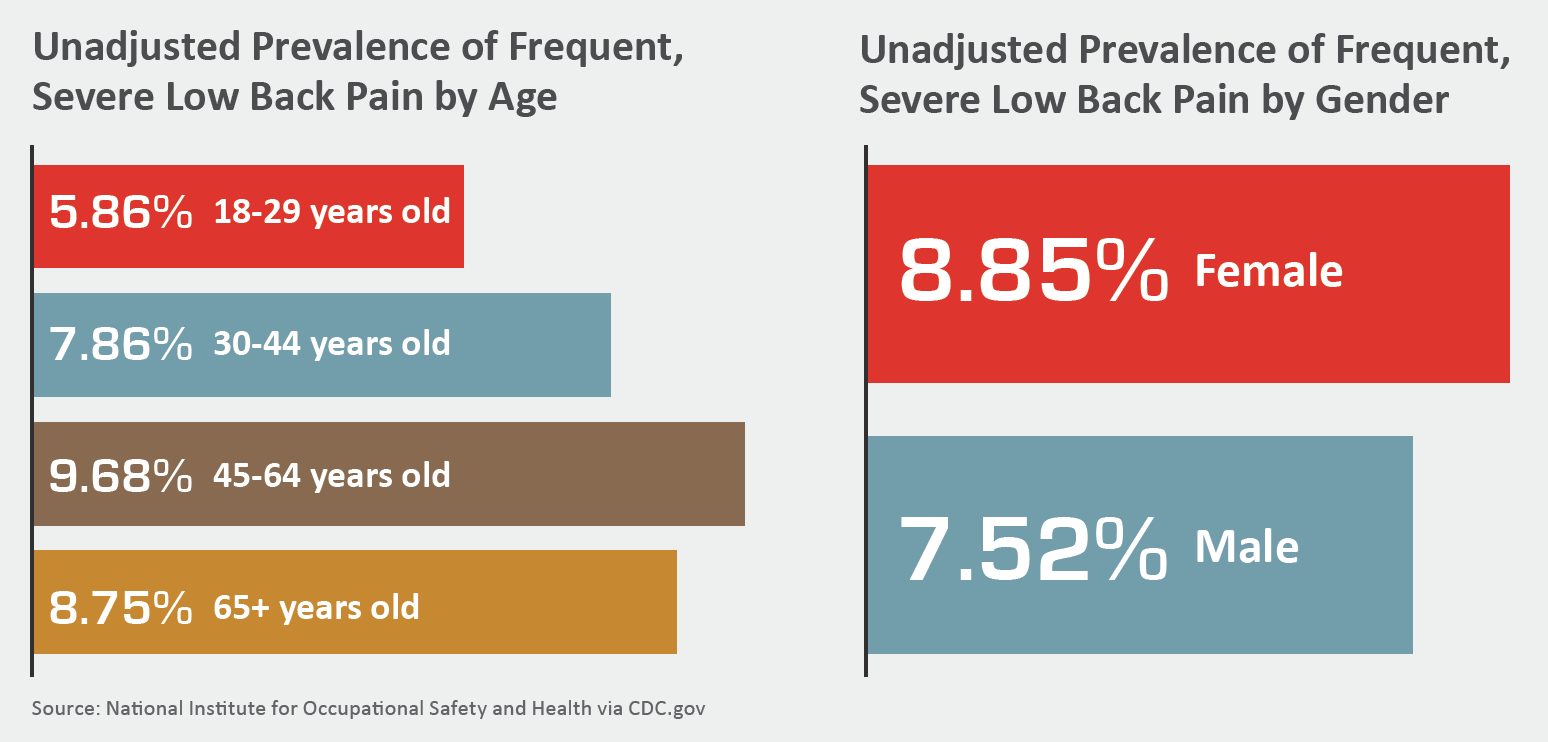

Jarvik points out that upwards of 80 percent of Americans experience low-back pain at some point in their lives. That’s a lot of sore backs, so any change in patterns of care for the complaint can yield major gains—or losses—at the level of population health.

Indeed, a 2016 JAMA analysis found that pain in the back and neck comprises the third largest clinical category of healthcare spending, at nearly $90 billion. Only diabetes and heart disease generate more costs.

What’s more, any interventions taken for back pain may end up being harmful, Jarvik says. He cites as an example a prescription painkiller addiction that, months or years later, traces to an initial scan of questionable necessity. “A cascade of unwanted effects can follow that scan with potentially enormous consequences in terms of both costs to society and disability to individuals,” he says.

Add to this potentiality the research showing unimproved outcomes despite all-but-unabated imaging—a Health Affairs study published in 2017 found a measly 4 percent decrease in “low-value” back imagining nearly three years after the launch of Choosing Wisely—and Jarvik’s recommendation moves beyond debate:

“More prudent use of spine imaging is critical,” he says. “And the easier we can make it to educate people about potential downsides of over-ordering lumbar spine imaging—the more radiologists can put into context what the findings actually mean—the better the chances for seeing more rational use of spine imaging.”

PAMA Alone Won’t Solve

Doctors ordering any nonemergent advanced imaging will soon have no choice but to think twice. As of January 2020, they’ll need to show they consulted evidence-based guidelines via a clinical decision support (CDS) tool in order to avoid payment penalties under PAMA, the Protecting Access to Medicare Act. Payment adjustments will kick in a year later, and private payers are sure to follow suit once the die is cast.

Jarvik notes that it will take more than just a mandate to ensure a meaningful experience for providers and patients and, when imaging is involved, radiologists.

“Ultimately, involving patients and radiologists in the decision about whether to order diagnostic tests is going to be important to the advance of shared medical decision-making,” he says. “This is where medicine needs to go.”

Jarvik and colleagues’ LIRE study should help with the effort. The work demonstrates the power of relevant benchmark information when it’s automatically incorporated into routine radiology reports, he explains. A lumbar spine MRI report, for example, would show the age- and modality-matched prevalence of various findings in people who don’t have back pain.

“It’s sort of like pathology defining what constitutes a normal range in lab tests,” Jarvik says. “It’s one way to do on-the-fly education for patients as well as practitioners. The time is right, as patients now have access almost universally to their imaging study results.”

Two Sides to the Story

Of course, there are times when it would be inappropriate not to order lumbar-spine MRI. Examples include patients with symptoms of a spinal infection such as vertebral osteomyelitis and those who have a radiculopathy (“pinched nerve”) persisting for six to eight weeks.

In the latter scenario, lumbar MRI “can be very useful in showing whether there’s focal nerve root compression that corresponds to the patient’s radicular symptoms,” Jarvik explains. “And if so, it may be reasonable to consider some sort of surgical intervention. So, for very targeted indications, lumbar MRI should be done and should prove useful.”

The problem has been that “we’ve used the exam for a host of other indications that are not as well defined,” he says. “Over time, that utilization has led to the overall perception that lumbar MRI is a low-value test. Like many technologies, MRI itself is neither good nor bad. It’s potentially both beneficial and dangerous. What’s good or bad is how we choose to use it.”