PET imaging technique detects brain inflammation after Lyme disease

Using an advanced PET imaging technique with a carbon-11-based radiotracer, researchers from Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore found as association with post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome (PTLDS)—a bacterial infection transmitted to humans through tick bites which effects roughly 300,000 people in the U.S. each year—and widespread brain inflammation.

Study findings published in the December issue of the Journal of Neuroinflammation may pave way for new treatments for long-term fatigue, “brain fog”, sleep disruption and other symptoms associated with PTLDS, which effects one in 10 people six months after being successfully treated with antibiotics for Lyme disease.

Lead researcher and psychiatry specialist Jennifer Coughlin, MD, and colleagues compared PET scans of 12 adult patients with a diagnosis of PTLDS and 19 healthy controls. All PTLDS patients had a history of confirmed or probable Lyme disease infection, documented evidence of treatment and no history of diagnosed depression, according to the researchers. The patients also had reported the presence of fatigue and at least one cognitive deficit, such memory or concentration problems.

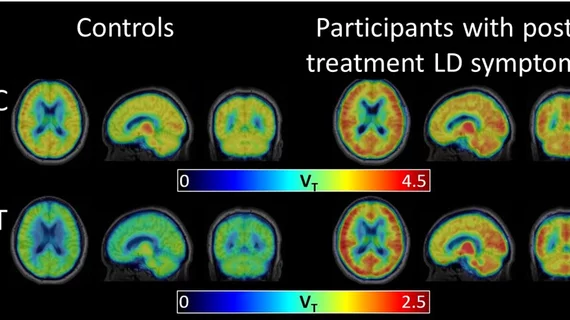

The team utilized a combination of PET imaging and the radiotracer carbon-11 (C-11) DPA-713, which specially labels molecules—or radiotracers—that bind to a protein called translocator protein (TSPO). This protein is released by two types of brain immune cells: microglia and astrocytes.

With this type of PET scan, the researchers were able to visualize levels of TSPO and, ultimately, levels of inflammation throughout the brain.

Brain scans of the PTLDS patients revealed higher levels of TSPO across eight different regions of the brain than the controls.

“There’s been literature suggesting that patients with PTLDS have some chronic inflammation somewhere, but until now we weren’t able to safely probe the brain itself to verify it,” Coughlin said in a prepared statement. “We thought there might be certain brain regions that would be more vulnerable to inflammation and would be selectively affected, but it really looks like widespread inflammation all across the brain."

The researchers noted, however, that their study was limited due to the small sample size. Also, the research did not include people who recovered from Lyme disease without developing PTLDS, but the researchers believe their results provide evidence that the brain fog in patients with PTLDS has a physiological basis and isn’t related to depression or anxiety.