The Surge Before the CDS Storm

If slow and steady really does tend to win the race over fast and fitful, then imaging-specific clinical decision support (CDS) software can, as a category, plan on a parade. Imaging CDS has long been widely considered a “when, not if” technology. But the smart money says to hold off at least a while longer before ordering, much less dropping, the confetti.

What’s the holdup? In a word, complexity.

Under the Protecting Access to Medicare Act (PAMA) of 2014, imaging service providers will, as of January 2020, still be reimbursed for advanced imaging exams performed in outpatient settings on Medicare recipients. However, these reimbursements will be limited to those ordered by referring physicians who used an approved, evidence-based imaging CDS system that leverages appropriate use criteria (AUC)—such as the ACR’s appropriateness-criteria guidelines, which are built into many EHR systems—to determine whether the exam up for order is right for the patient.

That may not sound like much, but there’s more. To comply with PAMA, imaging service providers must, in every instance in which advanced imaging services were delivered to a Medicare outpatient, provide documentation proving that the referring clinician consulted an approved imaging CDS system prior to the performance of the scan.

Not surprisingly, policy changes of this scope—sometimes coupled with other CDS initiatives—are leading hospitals, as well as the radiology departments and practices that serve them, to add imaging CDS to their technology arsenals.

While their collective experience in doing so has had its ups and downs, a number of imaging CDS stakeholders report forward motion in advancing a key part of the unfolding evolution: persuading referring clinicians to ride the imaging CDS wave.

Rocking Reimbursement

Rocking Reimbursement

Four years ago, the University of Virginia (UVA) Health System in Charlottesville integrated ACR Select, which applies the ACR’s appropriateness criteria to imaging orders, with its EMR’s order-entry components. The guiding goal was to elevate the quality of the institution’s care by ensuring appropriateness in imaging.

“The PAMA legislation didn’t prompt us to make the move to imaging CDS, but it made the transition a more credible initiative,” says Arun Krishnaraj, MD, MPH, who serves UVA Health as chief of abdominal imaging and vice chair for quality and safety. To date, he notes, feedback from referring clinicians has been notably positive.

“In addition to being accustomed to change, which is a regular occurrence within an academic hospital environment, referrers seem to appreciate the fact that, in imaging CDS, they have a tool to help navigate the litany of imaging exams and order tests from a base of knowledge rather than from a guess,” Krishnaraj says. “Imaging CDS also has had a positive impact on provider ordering habits, especially those of trainees.”

Results of a study co-authored by Krishnaraj and colleagues, published in JACR in March, back up his observations. The study details how, as part of UVA’s imaging CDS deployment, researchers mapped structured indications for imaging to exam appropriateness scores based on ACR Select. Referring providers using the system in inpatient and emergency settings (which in life-or-death situations will be largely exempt from PAMA reimbursement rules) were prompted to pick a structured indication for a particular study at the point of order entry. The CDS server was then queried, and an appropriateness score for the proposed study was generated and stored.

During the first six months of the study (“silent mode”), the CDS platform collected data but offered no feedback to ordering providers at the time of order entry. In the second phase of the study (“feedback mode”), upon ordering an exam, referring clinicians received real-time alerts indicating the utility of the study ordered, along with information on alternative exams.

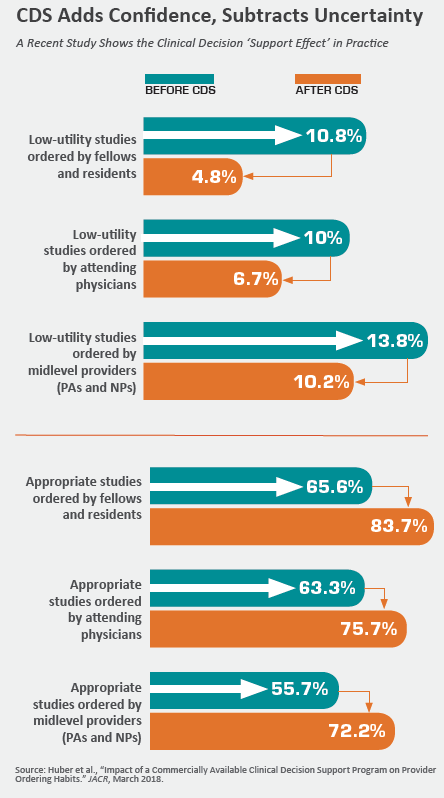

Access to imaging CDS produced a significant improvement in imaging study appropriateness scores, especially for exams ordered by residents and fellows, Krishnaraj and co-authors report (Huber et al., “Impact of a Commercially Available Clinical Decision Support Program on Provider Ordering Habits”). Comparing silent mode to feedback mode, they found low-utility studies ordered by trainees decreased from 10.8 percent to 4.8 percent. At the same time, clinically warranted (i.e., “indicated”) studies increased from 65.6 percent to 83.7 percent.

Using the same comparison, low-utility studies ordered by attending physicians and midlevel providers (physician assistants and nurse practitioners) decreased from 10 percent and 13.8 percent, respectively, to 6.7 percent and 10.2 percent, respectively. Appropriate studies ordered by attending physicians rose from 63.3 percent to 75.7 percent, while the percentage of indicated studies ordered by midlevel providers increased from 55.7 percent to 72.2 percent.

“Locally developed or institution-specific CDS software that has been implemented at several institutions across the U.S. has demonstrated that ordering patterns can change, with reductions in the number of low-utility examinations ordered after implementing such systems,” the authors write. “Our study demonstrates that similar results can be achieved with commercially available CDS and that the impact of these efforts can vary by provider type and imaging modality.”

Show Beats Tell

Sabiha Raoof, MD, chief medical officer, patient safety officer and radiology chair at Jamaica Hospital Medical Center and Flushing Hospital Medical Center in Queens, N.Y., reports similar experiences, albeit with a few bumps along the way. “When we first started with imaging CDS, there was some resistance from referring clinicians because of concern about workflow and the necessary extra ‘click’ to use the system,” Raoof recalls. The referrers’ qualms dissolved, she says, “once they saw how CDS improved the appropriateness of imaging, with communication and education on our part.”

Much the same happened at Triad Radiology Associates, which serves eight hospitals and nine outpatient sites in and around Winston-Salem, N.C. Triad radiologist Lauren Golding, MD, says the decision to use CDS tools to assess imaging appropriateness initially caused consternation among some referring physicians. The few probably spoke for the many when some grumbled over perceived loss of autonomy. That tension dissipated in fairly short order, Golding says, when the system showed itself to be a reliable, evidence-based way to either validate ordering decisions or help make better ones.

“It also helped that, with complicated cases, CDS became a trigger for discussing the right test with a radiologist,” Golding says, adding that subsequent use of the technology has prompted “positive conversations, not conflict, between radiologists and referring clinicians.”

Not all adoption is easy, of course. Golding and Raoof point to hospital emergency departments as a source of ongoing friction over imaging CDS. “In the emergency department, there’s a lot more pushback against imaging CDS because of the nature of the cases,” Golding says. “Physicians see their patients, know what they want and want it ordered. There’s no giving the system a say in the matter. It’s a continued topic of discussion.”

Krishnaraj notes that opposition to CDS also can pop up in situations where the criteria on which it’s based are weak or incomplete. He cites as an example a pronounced wariness among pediatricians that seemed widespread until around a year ago, when the Society for Pediatric Radiology updated its appropriate-imaging criteria.

Other scenarios of possible trouble are clinical trials that involve referrers treating study populations. These can produce pockets of reluctance to embrace, as Krishnaraj puts it, “something not routine, where a referring doctor may encounter unnecessary obstacles to obtaining a study that is really justifiable while the CDS is unaware of the details of the trial.”

Not Just Rebadged RBM

Not Just Rebadged RBM

Legislation or no legislation, pushback or no pushback, “selling” referring clinicians—and other stakeholders, including hospital administrators—on imaging CDS frequently entails extra effort from radiologists. Those successful in the drive tend to understand and anticipate referrers’ objections, in the process building a sense of collaboration.

Providing ordering clinicians with a “crash course” in imaging CDS, for example, can begin with an explanation of how the technology differs from that used by radiology benefits management companies (RBMs).

“Some referring physicians don’t quite understand that imaging CDS systems are evidence-based and were created by physicians with the objective of ensuring that imaging is necessary and that the appropriate patient receives the right exam,” Krishnaraj says. “They equate CDS systems with RBM solutions, which they think of as a ‘Big Brother’ technology designed to reduce costs without thought to much else. We can’t get where we need to go with imaging CDS without separating the two.”

When UVA Health introduced imaging CDS, Krishnaraj and his radiology colleagues “played the education card,” a naturally hard-to-resist move in academic medicine. They gave presentations aimed at filling in clinicians on the basics and benefits of the technology, and much the same material went online as a lecture series for specialists and primary-care doctors on a physician web portal.

At Jamaica and Flushing Medical Centers, radiology began its imaging CDS education outreach at the executive level, then took steps to make sure it would “trickle down” to department chairs, directors, managers and staff. Topics covered ranged from how the technology works to the ways in which it leads to a better match between patients’ clinical situations and referrers’ diagnostic choices.

With administrators, Raoof and her colleagues took extra time to discuss the Medicare mandate for imaging CDS adoption. They emphasized the importance of immediately moving forward with CDS and the implications—for cost control as well as care quality—of delaying such an initiative.

“When it comes to imaging CDS, getting hospital decision-maker buy-in through education and communication is essential,” Raoof says. “Once administrators are clear on the reasoning, there’s no choice about accepting it, and all the pieces with the remaining clinicians fall into place.”

Rightly Thwarted Workarounds

Equally key is carefully configuring the imaging CDS to suit its users’ universal and particular needs, the experts agree. Two Johns Hopkins radiologists flesh this out in an article published in JACR in February. Jeff Jensen, MD, and Daniel Durand, MD (who has since moved on to Baltimore-based LifeBridge Health), note that, without careful consideration for imaging CDS design, the technology’s deployment “will lead to increasing frustration, without achieving the intended purpose of optimizing imaging appropriateness. Conversely … with meticulous planning and strategic implementation tailored to the individual needs of a healthcare delivery system, imaging CDS can serve as an effective tool for both patients and members of the health system.”

In the article, titled “Partnering with Your Health System to Select and Implement Clinical Decision Support for Imaging,” Jensen and Durand recommend ensuring that every imaging CDS system offers complete, comprehensive guidelines for ordering imaging studies. The aim, they note, is to maximize its utility while minimizing frustration among clinicians.

Other system “must-haves” on this front include flexibility when it comes to imaging requests scored as “inappropriate” by the technology. According to the authors, the solution should be versatile enough to give end-user entities a choice of where hard and soft stops will occur in the ordering process. For hard stops, Jensen and Durand suggest, a radiologist must be consulted before an imaging exam is authorized; for soft stops, the original imaging request must be cancelled and another, more appropriate alternative must be ordered.

Additionally, the authors suggest that CDS systems feature an override mechanism for hard and soft stops alike, because variability in clinical circumstances is always possible—and not all imaging requests should be expected to meet established guidelines for a particular scenario. They also recommend making speed and ease of use a criterion for CDS configuration, with minimal mouse clicks required and no extra screens or pop-ups incorporated into the design.

Failure to address “cumbersome, time-consuming entry processes,” they write, will result in “work-arounds” or other attempts to fool the system—and poor clinical decision-making at best. To illustrate the point, they cite the example of a CDS system in which indications were organized as checkboxes and listed in alphabetical order. The implausible end-result in this case: “acromegaly” became the leading indication for head CT.

A final consideration flagged by Jensen and Durand centers on modification of clinical rules. While some radiology constituents strongly believe that an imaging CDS platform should allow local editing of guidelines and standards, there are reasons to prohibit such changes. Reason one: Modification of this type generally “forces the clinical rules themselves to be suboptimally integrated into the EHR platform,” rendering the decision support accessible only through a web service that typically requires launching another window. Such an interface is inconvenient to use, the authors point out. And inconvenience is sure to make any tool unpopular with referring physicians.

Reason two: Allowing local editing of guidelines defeats their purpose “as a collective set of benchmarks for imaging appropriateness that constitute a consensus, evidence-based standard.” The undesirable result, the authors point out, might be more arbitrary guidance based on local preferences. “This is not to say that the CDS workflow cannot allow deviation from national consensus on particular guidelines,” Jensen and Durand explain, “but the process itself should accurately document these deviations from consensus standards for the purposes of accountability.”

Smart CDS Makes Its Own Friends

Both Raoof and Golding have found that gradual deployment and a willingness to make initial concessions contribute to a more positive experience with imaging CDS. Imaging CDS implementation at Jamaica and Flushing Medical Centers began more than two years ago on the inpatient side and is now improving operations for radiology and cardiology alike. After the technology had been in place at both hospitals for one year, project leaders extended the rollout to all 12 offsite outpatient facilities affiliated with the institutions. CDS implementation in the hospitals’ emergency rooms is currently ongoing despite lingering ER-physician reticence. “We’re finally getting a bit of buy-in,” Raoof says, “and we hope it takes off soon.”

The hope seems well placed. At first, referring clinicians had the option to consult a radiologist with questions about the system, Raoof explains, such as why particular procedures were scored as inappropriate. Just as significantly, she and her colleagues maintained open lines of communication with referring clinicians throughout the hospitals, encouraging them to share information on any indications they wanted to add to the CDS system.

“There was a lot of back-and-forth with the ACR about it, but it was time well spent,” Raoof says. “Being able to accommodate the referring clinicians made them more receptive to the idea of CDS and contributed to a higher rate of acceptance” than might otherwise have been the case.

Meanwhile, referring clinicians at the hospitals and freestanding facilities serviced by Triad Radiology Associates were allowed to override the CDS free-text field for the initial few months following its introduction in February 2018. However, Golding says, workarounds of this kind are now being phased out. In the emergency room environment, there are currently no hard stops.

“We will probably never have the system set up so it says, ‘No, you can’t do this test, period,” Golding says. “And that’s probably for the best for the sake of a high acceptance rate. The hard stops do need to be incorporated, though.”

Going forward, as imaging CDS finds a following one provider organization at a time, radiologists and referring physicians alike will continue to face challenges as they seek to wring the full potential from the care-improving, cost-controlling technology. But isn’t that always the way?

“Radiology should be an active voice in the selection and configuration of CDS solutions for imaging,” Jensen and Durand conclude in their article, which may well constitute an essential read for anyone with a dog in the proverbial CDS fight. “Considering stakeholder interests and the needs of the healthcare delivery system, radiologists should be proactive in ensuring that CDS is configured in a way that facilitates lasting, collaborative relationships with referring physicians and highlights the value of the radiologist as a clinical consultant rather than a clinical commodity.”