Private Equity and Radiology: The Bloom Is on the Rose

A wave of consolidation is sweeping over physician practice specialties and, by many indicators, radiology may be next. Emergency room physician groups, anesthesiologists and hospitalists are being steadily acquired by large practice consolidators, hospitals and insurers, or, in some cases, by financial buyers like private equity firms.

Nearly all of these transactions are driven by the same set of changing industry dynamics: the need to achieve scale and market share in order to maximize negotiating leverage, compete for patients and manage costs; a desire on the part of hospitals to have their outsourced physician groups under one well-capitalized organization; the move away from traditional fee-for-service pricing models to flat episode and risk-based forms of pricing (so-called “bundled payments”); and the growing requirement for investing in technology to effectively track and manage patient outcomes as well as the business broadly. This, in turn, is a function of the economic model contemplated by the passage of the Affordable Care Act (ACA).

The current cycle of physician practice mergers and acquisitions (M&A) accelerated dramatically in 2010 with the passage of the ACA, and was initially concentrated in emergency medicine (EM). From 2010 through the end of 2015, there were 57 transactions involving emergency physician groups, with practice consolidators like TeamHealth and EmCare being the most common acquirers. As a result, today roughly 25% of practicing EM physicians work for a large national consolidator.

Anesthesia was the next medical specialty to attract serious attention from consolidators. Acquisitions here hit a record in 2014, with 29 transactions closed during that year. Activity was steady in 2015, when 26 transactions closed.

As a specialty group, anesthesia trails roughly 5 to 10 years behind EM in consolidation, with just 8% of practitioners working for a national consolidator. We expect this sector to continue to consolidate, with 20 or more transactions again this year and the number of anesthesia groups with over 100 providers that seek to sell increasing, as it has every year for the last three years.

Where is radiology?

Radiology is early in the M&A cycle, but all indications suggest that consolidation here will accelerate over the next few years. The market is highly fragmented, with about 27,000 radiologists generating $18 billion in annual revenue, and independent groups accounting for roughly 45% of the business.

About 75% of radiologists outside of academic institutions are in private practice, with hospital employment on the decline. At the same time, imaging utilization is growing exponentially, driven by new technologies and modalities, expanded applications, and the aging population, among other factors.

Consolidation has been occurring, but with no clear national players emerging yet. A number of factors have contributed to the relative dearth of radiology transactions over the last few years, including an uncertain reimbursement environment, ongoing cost pressure from payors and a shortage of capital on the part of some potential consolidators. Now, however, the business climate is more stable, capital is readily available, and new deep-pocketed buyers have entered the market through the acquisition of some of the less well-capitalized organizations.

There has been a corresponding uptick in transactions, though the numbers are still modest. In 2015, there were nine radiology transactions. The buyers included Sheridan Healthcare (a division of AmSurg), with two radiology acquisitions during the year; MEDNAX, which has been an active acquirer of anesthesia and pediatric physician specialty practices; and several regional consolidators. In 2015, publicly traded MEDNAX bought vRad, one of the early consolidators in the market with approximately 350 physicians and 2,100 facilities served.

By contrast, there was just one acquisition in 2014 and four in 2013. There has been one announced transaction so far in 2016—the acquisition of Advanced Medical Imaging and Teleradiology by strategic buyer Rapid Radiology in January.

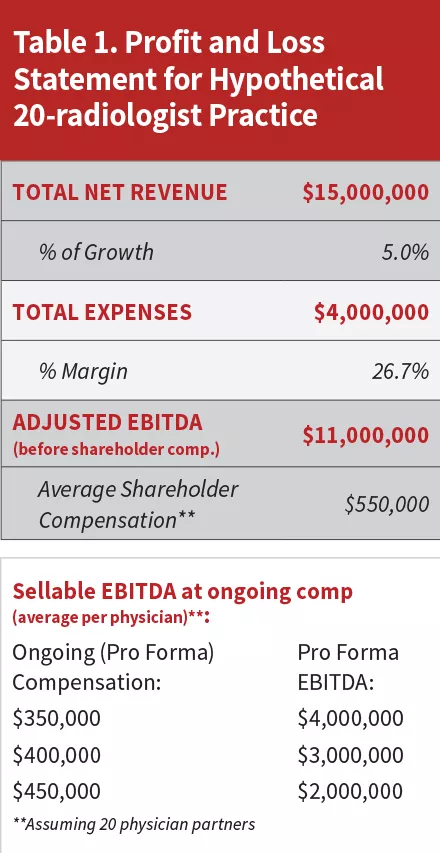

Transactions are generally structured to create sellable earnings on the basis of foregone future partner compensation. Partner compensation is reduced to the market compensation cost required to recruit and retain a comparable non-shareholder physician. The pool of earnings generated, the difference between partner compensation and employed physician compensation, is effectively the premium compensation that shareholder physicians receive for being owners and is referred to by many as earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA).

Post-transaction compensation for equity owners is generally in the range of $400,000 with additional upside possible depending on the performance of the group. The valuation for the practice is a multiple of this EBITDA that is often paid as a lump sum at the time of the closing of the transaction.

While the relatively small number of transactions makes it difficult to specify valuations, a few general patterns are starting to emerge. As might be expected, larger groups tend to command a higher multiple: 7-8 times earnings (EBITDA) compared to 6-7 times for midsized groups.

Overall, healthcare services public market valuations remain above their 20-year average, even after the recent market correction. In the current cycle, valuations for publicly traded healthcare services providers peaked at about 13.2 times EBITDA, before settling back to the current 10.5. Longer term, the average has been just under 9.2, so current valuations in the public market still reflect a 15% premium over the long-term average. As noted, private radiology practice valuations are at a discount to publicly traded companies, but still reflect a commensurate premium over the long-term valuation averages for privately held healthcare services businesses.

To sell or not to sell

As consolidation accelerates, more practice owners will find themselves facing the question of whether or not to sell, a decision with major personal and financial implications. For some physicians, pride of ownership and independence will trump all other considerations. For others, the potential benefits of a sale will prove compelling. In either case, the exercise is a valuable opportunity to honestly assess where you and your practice stand—strengths, weaknesses, and, most importantly, your ability to access the resources needed to stay competitive and grow.

Among those physician groups that have elected to sell, the most frequently cited reasons include:

- The changing healthcare environment, with the percentage of independent versus employed physicians declining rapidly, and growing uncertainty regarding future reimbursement patterns and income. The desire to be part of something bigger, with corresponding income security and negotiating clout.

- The ability to share and learn from best practices on both the clinical and the business side.

- Access to growth capital and business management expertise.

- A once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to monetize practice value.

- Attractive tax-rate arbitrage coming from exchanging a stream of income taxed at ordinary income rates for a lump sum payment today taxed at long-term capital gains rates. An added benefit is the time value of money coming from receiving a lump sum at closing versus a stream of payments over time.

- Hospital contract security through access to resources to meet turnaround time demands, quality, analytics and subspecialty demands; and leveraging existing consolidator relationships in hospital/system.

- The potential for some level of local practice autonomy.

- Access to a practice-growth platform based on consolidator resources and analytics, and the scale to pitch, win and staff new facilities.

Below are two tables illustrating the financial calculus behind the sale of a hypothetical radiology group with 20 practicing shareholder physicians, and annual net revenues of $15,000,000. Non-shareholder expenses of $4 million leaves profit for the partners of $11 million for an average compensation of $550,000. Reducing that compensation to $400,000 on a go-forward basis result is $3 million in EBITDA, which when valued at 7x in a sale transaction results in a $21 million in purchase price to be divided amongst the 20 shareholders, leaving each shareholder with $1.05 million in pre-tax cash and compensation of $400,000 per year going forward (Table 1).

Factoring in the tax arbitrage between ordinary income and capital gains but excluding any investment income earned on the proceeds, the transaction becomes a financial breakeven 9.3 years later, meaning that for the next nine years, the physicians in this group are financially better off having done the transaction, all other things being equal (Table 2).

Conclusion

The pressure on radiologists and other practice groups to manage costs, invest in technology and maintain and grow relationships with hospitals, insurers and other healthcare constituents is not going to ease anytime soon. The path of future consolidation is likely to resemble that experienced previously by EM and anesthesiology practice groups. The key for radiologists is to understand the forces at play and the factors that drive the decision to stay independent or to join with a larger group.