Challenges and opportunities in breast-imaging economics

In breast imaging practice we seek to provide care that is compas-sionate, patient-centered and evidence-based. The top aims are always to save lives and minimize the impact of breast cancer. As is true across U.S. healthcare, the economic environment for breast imaging is complex and evolving. Understanding these economics allows us to best address challenges and embrace opportunities to provide care that improves patient outcomes. To that end, here’s a look at some key aspects of breast imaging economics in play today.

CPT Codes and Payments

There has been much recent activity in the breast imaging Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes and payments maintained (and copyright-protected) by the American Medical Association. In calendar year 2017, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) adopted new CPT codes for diagnostic and screening mammograms (77065, 77066 and 77067). Also in 2017, CMS introduced new bundling of computer aided detection (CAD) with the mammogram services. Thus, the new mammogram codes include CAD when it is utilized, and there are no separate codes or payments for CAD.

For 2018, the CMS Medicare Physician Fee Schedule continues the 2017 CPT codes for breast imaging, including the add-on codes established in 2015 to be used when digital breast tomosynthesis is employed for screening (77063) or for diagnostic (G0279) mammograms.

CMS payments for breast imaging services in 2018 remain relatively stable compared to 2017. Overall, 2018 global payments are within 1 percent of 2017 payments for mammograms, ultrasounds and biopsies. The 2018 global payment for bilateral breast MRI is 6 to 7 percent higher than in 2017. In a setting of limited resources, the stability of breast imaging payments is good news for practices and for patients.

Potential payment challenges remain, such as the 50 percent reduction in the technical component of mammogram payments that was proposed in 2017, which would have negatively impacted patient care. The American College of Radiology (ACR) conveyed to CMS the likely patient-care implications of this change, such as reduced patient access. Favorably, this reduction was not enacted in 2017 and is also not present in the 2018 fee schedule.

Specialty-Specific Considerations

Payment for digital breast tomosynthesis mammograms has been challenging for practices and patients. The add-on CPT codes for tomosynthesis were established in 2015, and research studies have shown that screening with tomosynthesis added to full-field digital mammography improves diagnostic accuracy, results in health plan cost savings and is cost-effective per quality adjusted life year.

However, CPT codes and scientific evidence do not guarantee payer reimbursement. While CMS has reimbursed for tomosynthesis since 2015, private payers have been more limited in coverage. Recently, significant progress has been made in coverage across the U.S. Overall, tomosynthesis coverage for insured women across all payer types is now 70 per-cent or greater in most states (source: Hologic, April 2017).

Greater coverage has been achieved, in part, through state-mandated mechanisms. At the time of this writing, nine states had enacted mandated coverage of tomosynthesis. This has been accomplished by efforts of state radiology societies and leaders, by expanding the legislative or regulatory definition of mammograms to include tomosynthesis. Tomosynthesis is currently available at 44 percent of MQSA accredited facilities and on 29 percent of accredited units (Source: MQSA Scorecard, 12/2017).

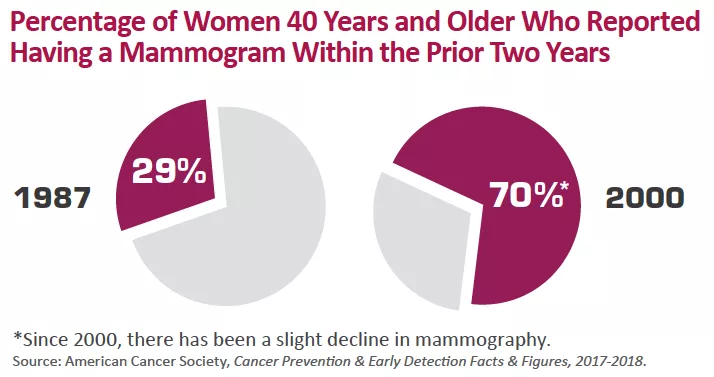

Further, concerns remain about continued screening mammography coverage for our patients. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) passed in 2010 requires private payers to cover screening mammograms with no cost sharing to patients. However, the ACA requires coverage of services with USPSTF grade “B” or higher.

As we know, the USPSTF recommendations for breast-cancer screening in 2009 and 2016 designated screening mammograms for women ages 40 to 49 grade “C” (and for women ages 50 to 74 screening biennially grade “B”).

This placed at risk the coverage of annual screening mammograms starting at age 40. There are now two mechanisms by which such coverage is preserved. The first is the Protecting Access to Lifesaving Screenings (PALS) Act, which places a moratorium on the ACA implementation of USPSTF recommendations. This measure was passed in 2015 and has been extended until January 2019. The second mechanism comes through ACA section 2713, which requires coverage of preventive services without cost sharing according to Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) guidelines. In 2016, HRSA guidelines were updated to specify screening mammography starting as early as age 40 years and as frequently as annually.

Other Broad Economic Trends

The economics of breast imaging reflect trends across medicine. Bundling of services remains a significant trend. The move from component to bundled coding and payment for services “typically” performed together is expected to increase.

Bundling is often associated with decreased reimbursement compared to the component model. In 2014, bundled breast biopsy codes resulted in a 30 to 50 percent reduction in professional payments. Of note, the 2017 bundling of CAD and mammograms did not result in decreased reimbursement compared to the component model. Further changes are likely in the future, such as bundling of breast MRI services with MRI CAD when performed.

Another trend in reimbursement is private-payer “steering” of patients to less costly locations of service. Anthem recently enacted policies in nine states to no longer routinely pay for outpatient CT or MRI in hospital settings. Instead, patients are “steered” to less expensive freestanding outpatient locations. Justifications and a review processes are required if hospital outpatient settings are selected. There are many limitations to this approach, including for patient access and continuity of imaging and clinical care.

We must work together to decrease unnecessary medical costs including in breast imaging, such efforts should not prioritize initial imaging test costs over quality or longer-term outcomes including cost-effectiveness.

Roll With the Changes

As across health care, breast-imaging economics are evolving. Our economic environment directly influences our ability to provide breast-imaging care for patients. We must work together to promote an economic milieu that facilitates best care and outcomes.

There are many ways we can participate to achieve this goal.

We should provide breast-imaging care that is evidence-based and is of highest quality and value. We should support the ACR, the Society of Breast Imaging, state society and individual efforts to achieve and maintain coverage which benefits patients.

And we should consider innovative economics models that can benefit our patients, such as bundling of breast imaging services on a larger scale from “screening to diagnosis.”

Dr. DeMartini, a past president of the Society of Breast Imaging, is chief of breast imaging at Stanford Medicine.