Good practice governance: 5 stumbling blocks and how to scale them

If it’s true that a house divided against itself cannot stand in any age, it follows that a poorly governed radiology practice is vulnerable against the pressures of healthcare economics in this age of consolidation, commodification and lingering uncertainty across U.S. healthcare. In this climate, every group needs to establish, implement and monitor policies for divvying up duties, doling out rewards and sharing decision-making. To fail at managing these matters is to invite erosion of your group’s prosperity, cohesion and, ultimately, its very viability.

“Without good governance and the structure behind it, there is chaos. And if there is success, it is despite what practices do, not because of what they do,” Lawrence Muroff, MD, president and CEO of Imaging Consultants in Tampa, told RBJ this spring. And on that point Muroff has been consistent for many years. In a landmark article JACR published back in 2004, he wrote:

“Radiology practices that are well organized and effectively governed have a competitive advantage. Decisions are made rapidly, actions are taken decisively and in accordance with established policy, and each group member has a responsibility for practice building. Such groups are perceived by their peers, hospital administration and community business leaders to be both formidable and effective.”

Nearly a decade and a half later, those observations are as apt as the day they were written. With that in mind, RBJ spoke with Muroff and other governance thought leaders on how best to govern a practice today, regardless of private vs. hospital setting. It turns out a sound strategy can be built around anticipating—and avoiding—some common stumbling blocks. Here are five of them, along with ways to get around each.

Stumbling block 1: Forgetting the foundation.

Scaling Strategy: Writing out a mission statement and business plan.

Governing a radiology group without a statement of purpose and a set of objectives is like living in a house built on stilts. Just as a concrete foundation underlays every edifice built to endure the elements, a mission statement and business plan comprise the cornerstone of effective radiology practice governance. That’s because they provide the basis for most decisions made within a practice, Muroff says.

Muroff suggests the optimal mission statement can be contained within a simple document. The wording need only succinctly define which individual practitioners constitute the group and what the group stands for. Example: “ABC Imaging Associates offers diagnostic imaging, interventional radiology and radiation oncology services to patients in the X area. We are committed to providing our patients with cost-efficient, easily accessible subspecialty expertise.”

In some cases, the mission statement also will include a geographical boundary. This helps potential patients decide whether it’s worth their time and travel to seek out the practice. Additionally, it helps the practice’s decision-makers figure out whether any future business opportunities presented to them are worth pursuing.

Meanwhile, the business plan lists specific goals that fit within the objectives in the mission statement and specifies how progress toward attaining those objectives will be measured. In the example of ABC Imaging, Muroff explains, a business plan for the upcoming year might lay out steps to win a contract for radiology services at a hospital or health system expanding in the area. It also might incorporate plans, whether general or detailed, to do things like initiate discussions with a hospital about a joint venture, recruit a certain number of fellowship-trained subspecialty radiologists, improve collection efficiency by a given percentage or reduce the age of accounts receivable by a certain number of days. It’s best to state goals contained in the business plan in at least fairly specific terms so that decision-makers can later determine whether or not the aims were met within the specified parameters and, if not, devise a strategy for addressing these issues.

Muroff recommends incorporating an “accurate assessment of the human resources needed for each project laid out in the business plan,” along with the “financial implications of all initiatives and tasks under consideration,” into the business plan. “This way, group members can figure out how each of these initiatives and tasks will impact the quality of their life, as well as their personal finances,” he says. “Some projects, like opening a new office, don’t become financially viable right away, and practice members need to understand the implications of the choices they make about them.”

Stumbling block 2: Dispensing with democracy.

Scaling strategy: Embracing the executive committee model—and doing so properly.

Group practices typically have a physician CEO at the top of the org chart, while academic practices look to a chairperson or director. Both types of practice require a board of directors or executive committee. “Putting all the decision-making power in the hands of a CEO is short-sighted and can make it appear to partners or shareholders, as well as to other employees, that decisions aren’t necessarily being made in their best interest,” says Kurt Schoppe, MD, a partner in Radiology Associates of North Texas in Fort Worth. “What’s more, a feeling of lack of control over what happens in a practice leads to burnout,” which can be detrimental to the health of that practice as well as to the caliber of care it offers patients.

According to both Schoppe and Muroff, it’s best not to elect members of a group practice’s board of directors or executive committee to indefinite terms of service, as the permanence can thwart fresh thinking from even taking shape. At Radiology Associates of North Texas, board members serve a three-year term. Those who have served three consecutive terms must be rotated, Schoppe explains, adding that the practice also elects a president for a one-year term.

Muroff’s 2004 article points out that the board of directors makes an “ideal training ground for future practice CEOs.” Consequently, he writes, “a balance of younger and more senior members constituting the board is desirable. In addition to age considerations, the board should also be representative of the demographics of the practice (geography, hospital vs. office, etc.).”

Other considerations are necessary to fruitfully embrace the executive-committee model in hospital-based practices. David Yousem, MD, MBA, associate dean and vice chair at Johns Hopkins, notes that executive committees sometimes bring in various subspecialty directors from radiology as well as section and division heads from within and even outside of radiology.

Well and good, but at academic medical institutions as large as Johns Hopkins, doesn’t such broad representation invite a “too many cooks in the kitchen” conundrum?

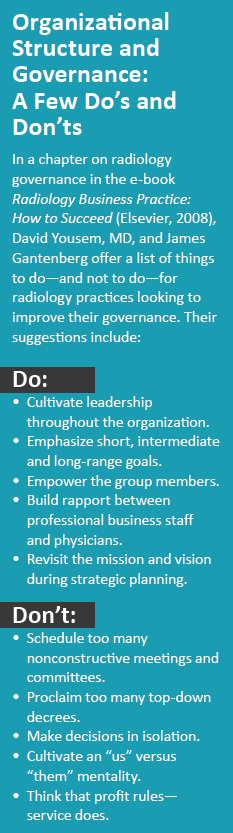

Yes and no. In a chapter on governance in Radiology Business Practice: How to Succeed, an e-book edited by Yousem and Norman J. Beauchamp, Jr., and published by Elsevier in 2008, Yousem and James Gantenberg, executive director and CEO emeritus of the American Society of Neuroradiology, write that seeking representation by section and division heads on the executive committee does indeed contradict the business-school maxim that committees whose ranks exceed eight to 10 members are often ineffectual. However, they assert, “the strong sense of ‘buy-in’ achieved by participation on the executive committee outweighs the lack of nimbleness that a large committee engenders.”

Stumbling block 3: Silencing some physician stakeholders.

Scaling strategy: Making sure all members of the group have a voice.

Giving all radiologists a say in how things are done within their practice has a positive impact on each member’s performance and, by extension, on the practice as a whole. So strong is that belief at Radiology Associates of North Texas that the practice’s bylaws differentiate between decisions that must be made by the board of directors and those that can be opened to everyone else. In fact, should 10 percent of member radiologists—whom the practice calls “shareholders,” as they hold a share of the corporate entity—object to a decision by the board of directors, the decision goes up for a shareholder vote.

“All it takes is a simple majority to overturn a decision by the board,” Schoppe says. “The benefit is that shareholders see the board as truly representing their interests.”

In Muroff’s view, the CEO and the board of directors can make most if not all routine operating decisions in a practice. Such an approach, he says, prevents group members from needless headaches over insignificant issues. It also saves a lot of time and increases operating efficiencies. Nonetheless, Muroff emphasizes that other group members should be engaged in putting together their practice’s mission statement and business plan, and in electing the CEO and board of directors.

Maintaining open lines of communication between shareholders, the board of directors and the CEO is essential in giving shareholders a voice, Schoppe says. At Radiology Associates of North Texas, the board of directors is not permitted to “make dictates,” he explains. Rather, board members are responsible for helping shareholders understand what decisions are being made and why, and for answering as many questions as necessary to ensure such understanding. Just as significantly, shareholders are encouraged to voice their concerns to the board of directors, and the board is charged with addressing those concerns.

Stumbling block 4: Turning a blind eye to academic medicine’s turf tensions.

Stumbling block 4: Turning a blind eye to academic medicine’s turf tensions.

Scaling strategy: Planning for pitfalls.

Yousem tells RBJ that, in academic radiology departments, the management tier below the chair typically comprises vice chairs of such departments as education, research, operations and, sometimes, faculty development. Business development or community practice chairs occasionally fall into the mix as well. The next layer of organization includes division or section chiefs. This tier is typically broken out by anatomic focus (e.g., neuroradiology, musculoskeletal, thoracic/cardiac, breast imaging).

Other chiefs, including a pediatric chief, interventional radiology chief, and nuclear/molecular imaging chief, may be “superimposed” above the division/section chief layer. Moreover, Yousem notes that, while the heads of these divisions may be in charge of faculty issues, there may also be physician leaders who are directors of specific modalities, such as CT, MRI and ultrasound, and they may interface with non-faculty department members.

Yousem cites as advantages of this organizational structure multiple opportunities for academic faculty to develop leadership within their area of expertise. He also points to increased faculty engagement and the ability to easily identify faculty liaisons to the various clinical services that refer patients to the radiology department.

Such arrangements do have disadvantages, however. These include the decentralization of leadership and a likelihood that turf-protective leaders may vie for the same capital equipment dollars and for influence in the capital equipment purchasing process.

When divisional silos are created in these settings, “the overall concept of the ‘department’ may be lost,” Yousem says. “This is problematic when traditionally lucrative divisions like interventional radiology are expected to support less profitable ones, like nuclear medicine.” In order to maximize effective governance, hospital-based radiology practices must embrace the advantages and try to minimize the disadvantages. This can be done by, for example, creating cross-functional committees to bridge the gap between silos.

In the book chapter Yousem and Gantenberg wrote on governance, the authors note the unlikelihood of full professors “go[ing] down without a fight … on most decisions, especially as they did not achieve their highly regarded status” through passivity. “[T]he creation of a functional committee structure can serve to empower the members of the group as well as to improve communication between constituents,” they add. “Breeding strong leaders in such an environment provides the ability for creating a group’s collective historical memory, which enhances good judgments in decision-making and prevents repetition of prior mistakes.”

Stumbling block 5: Choosing just anyone to serve as CEO or chair.

Scaling strategy: Picking with precision.

Practices need a CEO with administrative and management skills, Muroff maintains. “This person should be respected not only by members of the group but also by referring physicians and community leaders,” he says. Muroff adds that, in academic practices, one person usually serves as CEO of the radiology group and chair of the hospital radiology department. However, he believes this is not the best-case scenario. “It’s better to have two people,” he says, “for several reasons.” These reasons include:

- Community hospital negoti-ations can be adversarial. If the hospital chair functions as a “good cop,” acting willing to accommodate the hospital’s demands providing that the “bad cop”—aka the group CEO—will agree, the hospital chair can remain cordial in negotiations with hospital administration.

- In a community setting, referring physicians and hospital administrators often push to select as department chair a practicing radiologist who works mainly in that hospital’s setting. This does not work for large, multisite practices, Muroff says.

- Different skills are needed to administer a radiology practice and head up a radiology department. Those who do the former will be tasked with participating in managed negotiations, making business deals and interacting with the community—functions that may be out of academics’ wheelhouse.

The person at the top of the org chart, whether private practice or hospital department, “should be able to negotiate on behalf of the practice, in keeping with the mission statement and business plan,” Muroff says. “And it’s important to remember that the ability to perform all these CEO duties are independent of clinical skills—and the right person for the job isn’t necessarily the best clinical radiologist in a practice.”