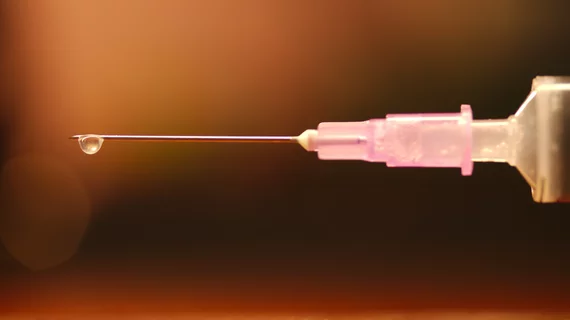

5 ways to avoid needlesticks in radiological settings

Needlestick injuries hit interventional radiologists at the rate of one incident for every five years of practice. This translates to around 90% of IRs getting an inadvertent jab at some point in their career.

Nor is diagnostic radiology immune to the likelihood. Also at risk are all radiologists, trainees and technologists who perform or assist in image-guided needle biopsies or intravenous contrast administration.

Researchers at the University of Maryland Medical Center report the figures and recommend preventive measures in a paper published online April 27 in Clinical Radiology.

“Even though needlestick injury is common in radiology, it is often not a part of a trainee’s education and may lead to delay in seeking appropriate care, underreporting and post-traumatic stress disorder,” write Clarissa Lin, MD, and colleagues.

The authors cite one study showing around 33% of such injuries going unreported. Common risk factors include being male, having a low-risk patient, trainee status, self-injury and previous needlestick injuries.

Outlining some of the major pathogenic threats transmittable via breaks in the skin—not least hepatitis B, hepatitis C and HIV—the team lays out five pointers for averting blunders:

1. Adhere to risk-reduction strategies common across healthcare. Not least among these are remaining mindful of established precautionary protocols, the need for extra caution in STAT situations and the onset of fatigue during long work hours, Lin and co-authors note.

“[R]adiology-oriented prevention can be made,” they offer. “For example, only 58% of radiologists who experience a needlestick injury had formal education on needlestick injury prevention. Therefore, adequate safety-first culture and training should be emphasized. Residents should have proper training prior to rotating on a procedural service and should rotate on a block schedule rather than mixed shifts.”

2. Use the right needle at the right time in the right way. Many if not most needlesticks occur just before or immediately after the patient has been jabbed, meaning while someone is preparing, recapping or discarding a needle. New devices with safety features have been growing in popularity, but they’re only as good as the training and familiarization by which they’re accompanied, the authors suggest.

Meanwhile, the team urges judicious use of larger-gauge needles, as blunt needle tips have been shown effective at reducing both injuries and infections. In fact, blunt needle tips should be used whenever possible, the authors advise. “For example, a blunt needle tip should be used to withdraw medication from a vial, and a blunt tip vacuum-assisted biopsy device should be used when performing MRI-guided or stereotactic breast biopsies after a tract has already been created and secured by an introducer.”

3. Handle all sharps with extreme care and focus. Foam blocks on procedural trays are fine as temporary holders for sharps, the authors state, but such stations should only be used for smaller items like scalpels and hypodermic needles—never for large tools like core-biopsy devices. The latter typically have heavy handles whose very weight can tilt the foam block, causing the tray to tip over.

Additionally, it’s best to avoid re-capping and re-sheathing, Lin and colleagues argue. If these steps are unavoidable, “there are safe re-capping devices and techniques that may decrease risk for injury. Other preventive measures include proper education on instruments being used, disposal of sharps with forceps rather than hands, and emptying the sharps bin when three-quarters full.”

4. Wear appropriate safety equipment when performing procedures—and that goes for ancillary staff as well as radiologists. Along with facemasks and/or face shields, the authors recommend wearing two sets of gloves and closed-toe shoes.

“With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been increased awareness about wearing proper personal safety equipment for procedures, particularly face shields and safety glasses. With heightened awareness to follow guidelines, proper eye or face shields can decrease the risk of fluid transmission to the mucosal surfaces of the eyes, nose, and mouth, decreasing transmission rates.”

5. Communicate, communicate, communicate. Thanks to social distancing guidelines occasioned by the pandemic, procedure rooms tend to have fewer healthcare professionals working closely together in procedure rooms. However, the need for coordinated teamwork has only become more acute, Lin and co-authors suggest.

“It is imperative to minimize passing sharps, such as an un-capped needle or biopsy device, to another person—but if it is done, one should use clear verbal communication and look at the sharp before reaching for it.”

More content on sharps safety:

‘Dramatic’ rise in image-guided procedures performed by NPs and PAs rather than radiologists

Survey unearths significant variation in practice patterns for localizing breast lesions

Reference:

C. Lin, M. Aljuaid, N. Tirada, “Needlestick injuries in radiology: prevention and management.” Clinical Radiology, April 26, 2022. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crad.2022.03.021