Rise of the athletic brain savers

A ripple of excitement lapped the football world last February when the FDA approved a blood test that could be used to detect concussion. At last an accurate tool had arisen beyond the cursory and subjective functional tests commonly administered after a player takes a blow to the head. Better yet, the objective clinical feedback could eliminate the need for radiation-exposing CT in at least a third of the cases for which head scans likely would have been ordered, according to champions of the new diagnostic test, known as the Banyon Brain Trauma Indicator. The test works by measuring two brain-specific protein markers that appear rapidly in the blood at elevated levels following a traumatic brain injury (TBI).

Not so fast, came the blowback from medical experts and clinicians who routinely handle concussed patients. Those markers are absent in the vast majority of individuals with concussions.

“The test is not really to diagnose concussions, but rather it’s a decision-making tool to indicate whether or not someone needs a CT scan after a head injury,” explains Mark Halstead, MD, director of the Sports Concussion Clinic at Washington University Medical Center in St. Louis.

Game-changer or not, the blood test may be significant for the buzz it generated and what that says about the direction of concussion diagnosis and treatment. Even if the new blood test isn’t the holy grail some proclaimed it to be, it at least represents a meaningful step toward assuaging the public’s growing concern over concussion. In this view, it’s comforting to know that medical science is trying to find more effective and sophisticated ways to detect and treat the injury.

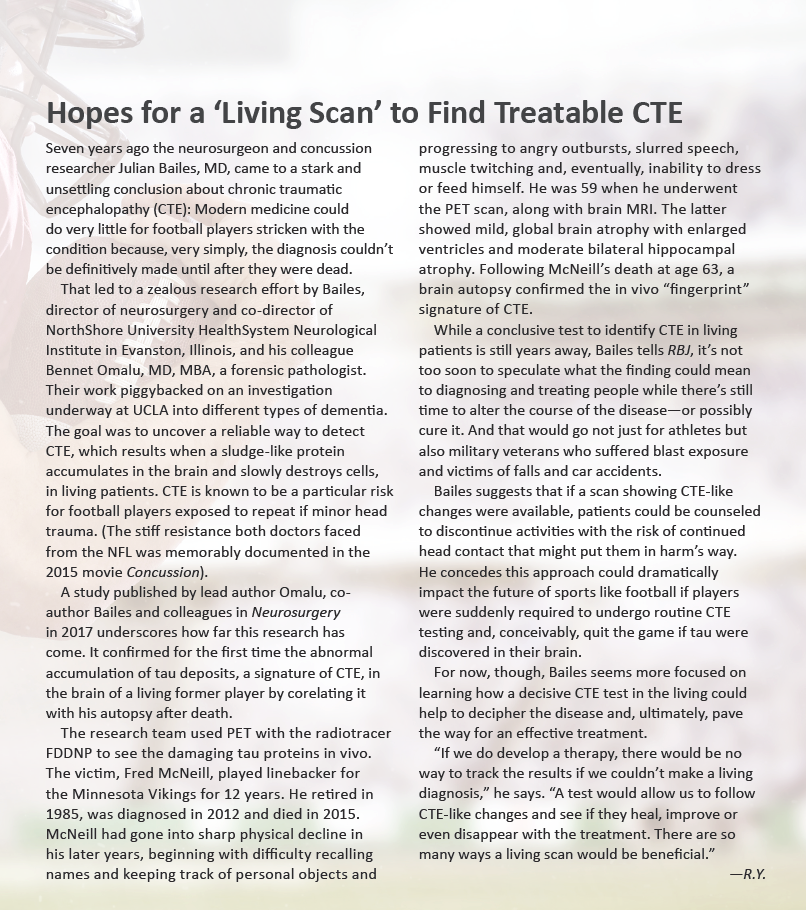

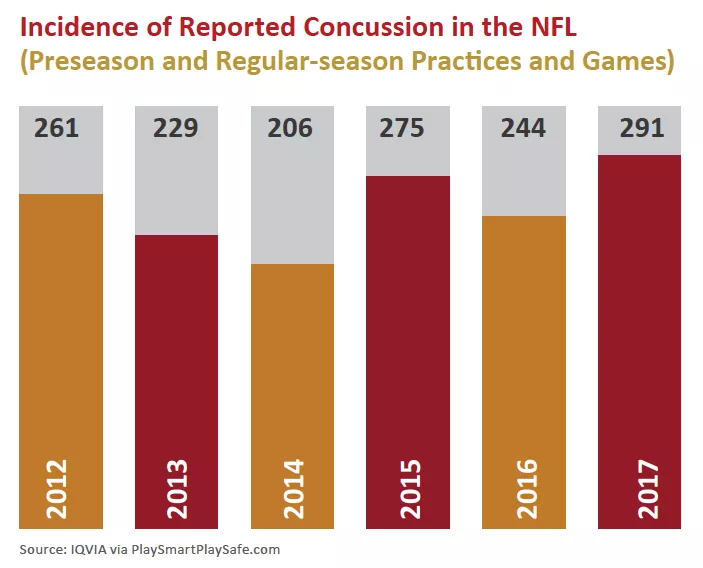

This is no small thing, as the Brain Injury Research Institute estimates somewhere between 1.6 million and 3.8 million sports- and recreation-related concussions occur in children, teens and adults in the U.S. each year. In the NFL alone, players and teams reported 291 concussions over the course of the 2017 season, according to IQVIA, an independent company retained by the NFL. Even if some of those cases went unconfirmed, that’s a lot of hard head blows for a league with just 1,700 or so active players.

The implications are considerable for radiology, which is clearly in the vanguard of what some are calling the “war against concussions.” Consider that in the not-so-distant past very few athletes who suffered severe head impacts received a focused assessment, much less a CT or MRI exam. Football helmets were essentially plastic shells with a modicum of padding on the inside. When a player took a nasty hit, the team doctor—usually an orthopedic specialist—performed a quick once-over.

“There wasn’t anyone there with the expertise to evaluate them and say, ‘Something is wrong,’” notes Anthony Anderson, a radiologic technologist who works Atlanta Falcons games on football Sundays. “If the player who sat groggy on the bench was able to count the number of fingers the doctor held up, then he was good to go.”

Nowadays every NFL team has a radiologist or neuroradiologist on their roster with expertise in concussion evaluation. On game days, a pair of neurologists and/or neuroradiologists prowls the sidelines of both the home and visiting teams. Meanwhile an athletic trainer eagle-eyes the field from an overhead box, searching for players who have sustained hard hits and taken a tad too long to get back on their feet. With a direct line to the referee on the field, these “concussion spotters,” who are independent of either team, can call a player off the field and into the locker room for physician evaluation.

The growth of concussion centers

The vastly heightened support NFL players receive on game day is only part of the evolving story of concussion management in and beyond sports and recreation. The other part is the growth of multidisciplinary concussion teams at a growing number of major medical centers around the country. These teams collaborate to examine and treat not just athletes but also military veterans injured by explosive devices, older adults who have fallen, drivers who suffer whiplash in car accidents and patients sustaining above-the-shoulders trauma in whatever setting it might occur.

Radiologists play an active role on these teams, working alongside neurologists, neurosurgeons, physical and occupational therapists, psychologists, ophthalmologists and speech language pathologists. All have concussion expertise and a specific role to play.

“We are critical members of any successful concussion center,” explains neuroradiologist Yvonne Lui, MD, of NYU Langone Medical Center’s Concussion Center, formed about four years ago. Depending on the severity of the injury, the Manhattan-based center may perform a CT scan or MRI. Lui or another neuroradiologist on the team carefully reviews the imaging to grade the more serious cases of TBI while ruling out other intracranial pathologies.

“We’re getting more sensitive to injury through better techniques like susceptibility weighted imaging and tailored protocols for head-injury patients,” she says.

Protocols are at the heart of the screening process for TBI. For example, new patients to NYU Langone’s Concussion Center, which is one of the earliest and largest programs of its type in the country, undergo a thorough neurological exam to check balance, coordination, vision, cognitive functions, smell and hearing. More than 75 percent of TBIs are considered relatively mild concussions, and patients will usually recover quite quickly. If physicians suspect a more serious case, one that could be life-threatening and require immediate treatment, including surgery, they will order a CT scan in the first 24 to 28 hours following the injury. This neuroimaging is highly effective in detecting bleeding within or surrounding the brain, swelling of the brain or skull fracture. If the patient’s condition persists or worsens, MRI may serve as a valuable alternative after 48 hours, lighting up injured areas that would remain hidden on CT. These include microhemorrhage, small areas of bruising and scarring (gliosis).

Findings from this extensive battery of neurological tests and imaging provide the template for a treatment plan at any concussion center or clinic, which means connecting the patient to the appropriate specialist.

At NYU Langone, members of that team are attached to the 4,000-square-foot Concussion Center. The advantages of this centralization are clear when weighed against past practice. In pre-center days, according to Lui, “clinicians often didn’t know what others were doing within the same system, much less across systems. Information could fall through the cracks, and it just wasn’t coordinated. That’s why developing a uniform approach is critical for treating any disorder, not just concussion.”

That thoughtful approach extends to the actual design of the facility. Lighting is dim, colors are tranquil and there are no televisions or other distractions that could prove uncomfortable for concussed patients. What’s more, dedicated program managers and coordinators help patients make appointments and access the center’s interrelated services.

Halstead, an associate professor of pediatrics and orthopedics at Washington University School of Medicine, affirms the importance of a concussion program stocked with trained professionals.

“The thing to remember about concussion is that there’s no one clinical group that owns the injury,” he says. “Whether they’re in-house or part of a network, you need multiple specialists who work together as a full-fledged concussion team.”

Halstead, for his part, trained in non-operative pediatric and adult sports medicine and is currently team physician for a number of high school and professional teams, including the St. Louis Blues of the NHL. As head of the sports concussion clinic, he gets ready access to an array of concussion-savvy specialists in and around St. Louis, from neuropsychologists to radiologists to physical therapists.

Radiology takes the field

As radiology becomes an increasingly vital part of concussion detection and management, its footprint within the field is expanding. All NFL teams have long had x-ray machines at their stadiums. More recently, though, most have upgraded from plain film to digital radiography, and all images are now PACS-networked across the league and entered into each player’s EMR.

At least three stadiums have CT scanners on site, and that number is certain to grow. Mercedes-Benz Stadium, new home of the Atlanta Falcons and the site of next year’s Super Bowl, will trial during this year’s preseason a small, 16-slice mobile scanner designed for imaging the head as well as extremities.

“In a normal x-ray of the skull you’re looking at bony anatomy, but this device will let us see minute levels of fluid buildup in a player who has a brain bleed,” says Anderson. “From that information we’ll be able to determine the extent of the concussion.”

Another example of radiology’s growing role in concussion care is the decision by several NFL teams to bring a radiologist to the annual NFL scouting combine, a once obscure event that has become a TV attraction in its own right. This by-invitation-only showcase draws hundreds of college prospects and allows NFL teams to evaluate the physical, mental and medical status of players they may want to draft. In recent years radiologists have become an integral part of this process, reviewing prior imaging exams embedded in athletes’ college records and ferreting out histories of concussion or other serious injury. On these radiologic findings could rest a player’s draft status, salary potential and, in fact, very future—or lack thereof—in football.

Research looks for causes, cures

Despite the progress that’s been made, diagnosing traumatic brain injury remains largely subjective, dependent on the clinical judgement of the radiologist and other medical specialists. There is still no single, gold-standard test to confirm if someone has a concussion. This vacuum is particularly vexing to professionals charged with making the difficult call.

“In not every concussion are the signs or symptoms outwardly visible, and that makes things pretty challenging,” says Halstead. “We’re relying on individuals to report their symptoms to us, rather than being able to rely on a test or exam that could say for sure if they have a concussion.”

Enter the new wave of concussion centers and clinics at major medical centers and hospitals nationwide, particularly in cities with high concentrations of professional sports teams. A critical part of their mission is research, no small undertaking in a sport where, according to the NFL’s own statistics, nearly a third of retired players will develop long-term cognitive problems.

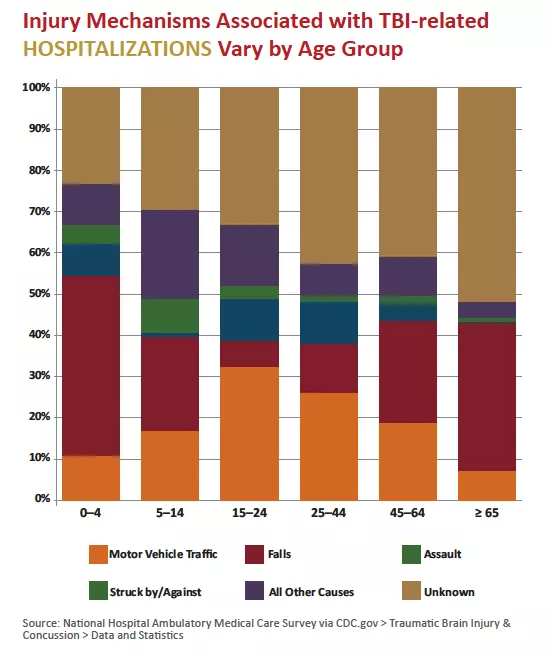

Numerous studies are underway to give clinicians a better set of tools and procedures to determine if an amateur or professional player is at risk. Researchers, for example, have confirmed for the first time through PET scans chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) in the brain of a living former player by correlating it with his autopsy after death. This represents a major step on the road to understanding how the disease develops, and how it could possibly be altered or even cured.

At NYU Langone’s concussion center, research is focused on rapid sideline screening, the impact of concussion on vision and brain processing, group therapy treatment, and improved ways to use imaging to get a better handle on concussion.

“We’re starting to better understand the underlying pathophysiology of concussion through advances in MRI,” says Lui. “It’s giving us the ability to probe tissue microstructure as well as metabolic and functional changes of the brain. This is important information because knowing what types of injuries are occurring allows us to find ways to recovery.”

Given the visible pace of change in a field that until recently could boast of very little, it’s not hard to see how the recently approved blood test for concussion could rightly be considered a milestone for football.